The Big Wave – Raphael Fonseca, 2011

Published in portuguese at the blog https://gabinetedejeronimo.blogspot.com/.

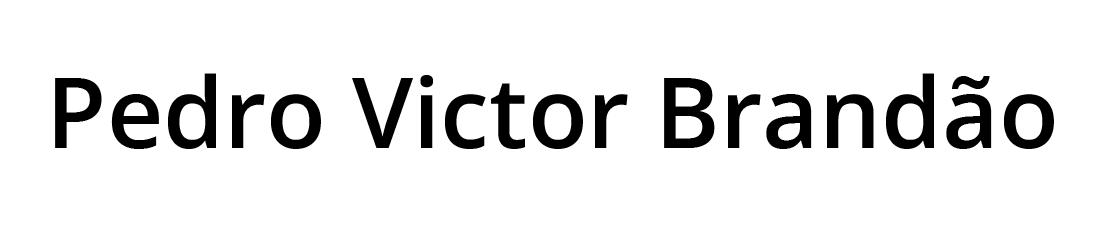

Between October 11th and November 6th is realized the exhibition “Pintura Antifurto”[Anti-theft Painting], by Pedro Victor Brandão, at Casa França-Brasil, at the center of Rio de Janeiro. It is another edition of the project Ocupação Cofre [Vault Occupation], by which contemporary artist from different generations deal with the space designated to the vault of the building projected by Grandjean de Montigny, that in the past was part of the Praça do Comércio [Square of the Commerce] and headquarters of the Alfândega [Customhouse] of the carioca port.

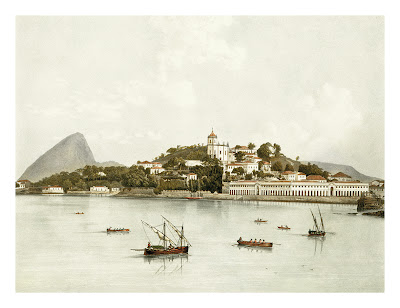

The work of the artist, at first instance, is different of previous occupation due to its explicit dialogue with the history of our patrimony. From the door it is possible to see a rectangle (56×156 cm) at the spectator’s eye level that fits the horizontal space of the front wall. Looking closely, we perceive that four rows of Real’s banknote images embody the geometric form. Twenty four banknotes by each line. Magenta and white are the tones of this mosaic. Below there is a stand where a series of these notes where available to the spectator, since the day of the opening. Now we deal with the emptiness such as the white of this “flag” of twenty and fifty Real banknotes. The recoded turn of the currency into the (phantasmatic) sacred space of the vault and now destined to contemporary art.

We can read this work through the relation between art and politics. Pedro Victor could individually shoot banknotes stained by the “anti-theft liquid” present at some ATM’s. In an attempt to break the structure of the machine, usually with the use of explosives, a magenta coloured liquid is released, impregnating the money and, therefore, due to the recent determination of the Central Bank, transforming it into mere paper. The image of the object resultant of a crime is transformed into art. That which legally has no more financial value goes back to its initial state; elevated to art status, it is likely to have value again, but already within the art market. Adding to the irony of this image, the artist lets the audience take home, free of charge, a particle of the mosaic. These spectators become collectors and, due to lack of a daily reposition of these copies (signed and serialized in the verse), they can now speculate on the possible values for their small works of art.

By what other means of access, however, can we read this exposition? Let’s go back to its titled: “anti-theft painting”. Is there any painting exhibited here? No, we have the photographic record of these notes that were not painted by chance (because of the intension of the violation), but in a “random” way. This work was built collaboratively; a robbery was necessary to happen so that these notes were stained. The ways how these ATM’s were violated are proportional to the different kind of magenta paintings. There is some kind of tension between photography and painting, technical and “artisanal” (only in pictorial title and not in the act, since it is a machine that performs the painting, even if triggered manually by humans). After completing the photographic clicks, Pedro Victor had a curatorial work: he chose the images that would give a body to his installation and with them made explicit the contrast between the stain and raw note. Thus, on the gallery wall we have the confrontation amid the color and the trace of the banknote’s death. The bones still deteriorate, but that does not make much difference; the corpse is already exposed.

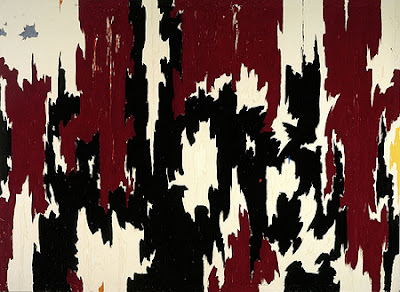

Formally, the organization of these white areas, which refer to layers of the same image, as if someone had ripped its surface, reminds of the painting of the so called “abstract expressionism.” An “organized disorder” and a weight thought to the colors seen, within this historical period to work, punctually at Clyfford Still’s work. Stalactites, mountains or fable? Ultimately, landscape. The horizontal character of the image contributes to this apprehension. Its format dialogues directly with the classical landscape painting, monumental or private, but always with the intention to be a window and show the public the extent of an area, its panorama.

This way of building the visuality was received and configured by the still incipient photography during the nineteenth century. From one Victor to another. One of the photographs taken by Victor Frond subsequently transformed into lithography for the book “Picturesque Brazil” (1858-1861), is an overview of the “Entry of Guanabara Bay.” The immensity of the sky, the discreet but lush carioca tropical landscape and the vessels queued to approach, possibly, the Port of Rio de Janeiro. And where is held the exhibition of Pedro Victor Brandão? Just in the building that once the Customs of that port was headquartered. Just as ATMs and banks, ports are also spaces of financial exchange. Accordingly, the detached notes offered by the artist become small postcards of his (now) fictional landscape. The carioca nature is equally anti-theft; any attempt to record it will always be mere trace, as well as those fragments of photo paper. From the foreign and exoticizing look of an artist about a city to the target on the status quo of violence and economy in the safe harbor of another photographer.

In the bottom of the central image of “Anti-theft Painting”, the contrast occurs in a punctual way: small “white stains” alongside of what really is the stained area; above, an increased contrast given by the continuous extension of white. The wet sand after encountering the water and a big wave is announced between the horizon and the margin. Tamarins are no longer golden, ounces have their spots erased. There is no more space for the calm apprehension of Guanabara Bay. It is necessary to swim against the tide, climb this big wave and prevent it from becoming a social seaquake.